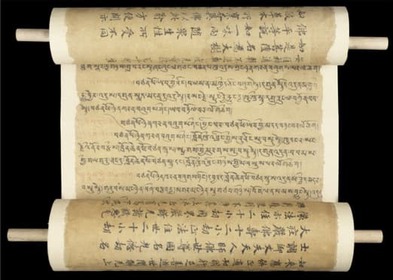

IOL Tib J 750 : Copyright of the British Library, courtesy of IDP

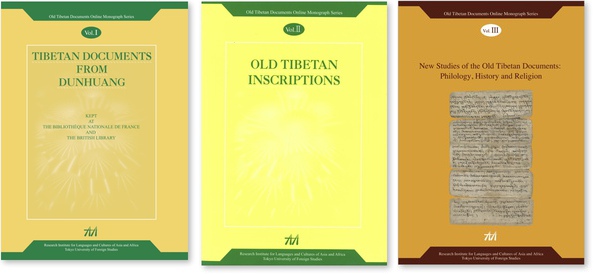

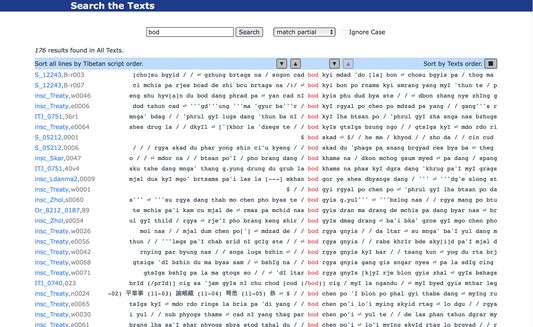

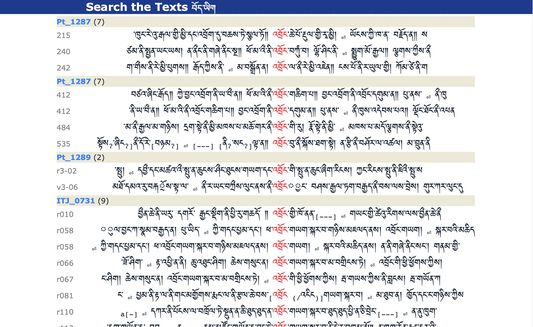

Old Tibetan Documents Online (OTDO) is a corpus of selected Old Tibetan texts (VIIth to XIIth centuries): Dunhuang manuscripts, Inscriptions and related materials. We provide critically edited texts together with search and KeyWord In Context (KWIC) facilities.

It currently contains:

The beta version of e-texts in Tibetan characters in UTF-8 coding is also available (⇒ Old Tibetan Documents Online བོད་ཡིག).

Funded by the Information Resource Center (IRC), it is based at the Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA) at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

News